I bet you’ve seen a “graph” like this somewhere.

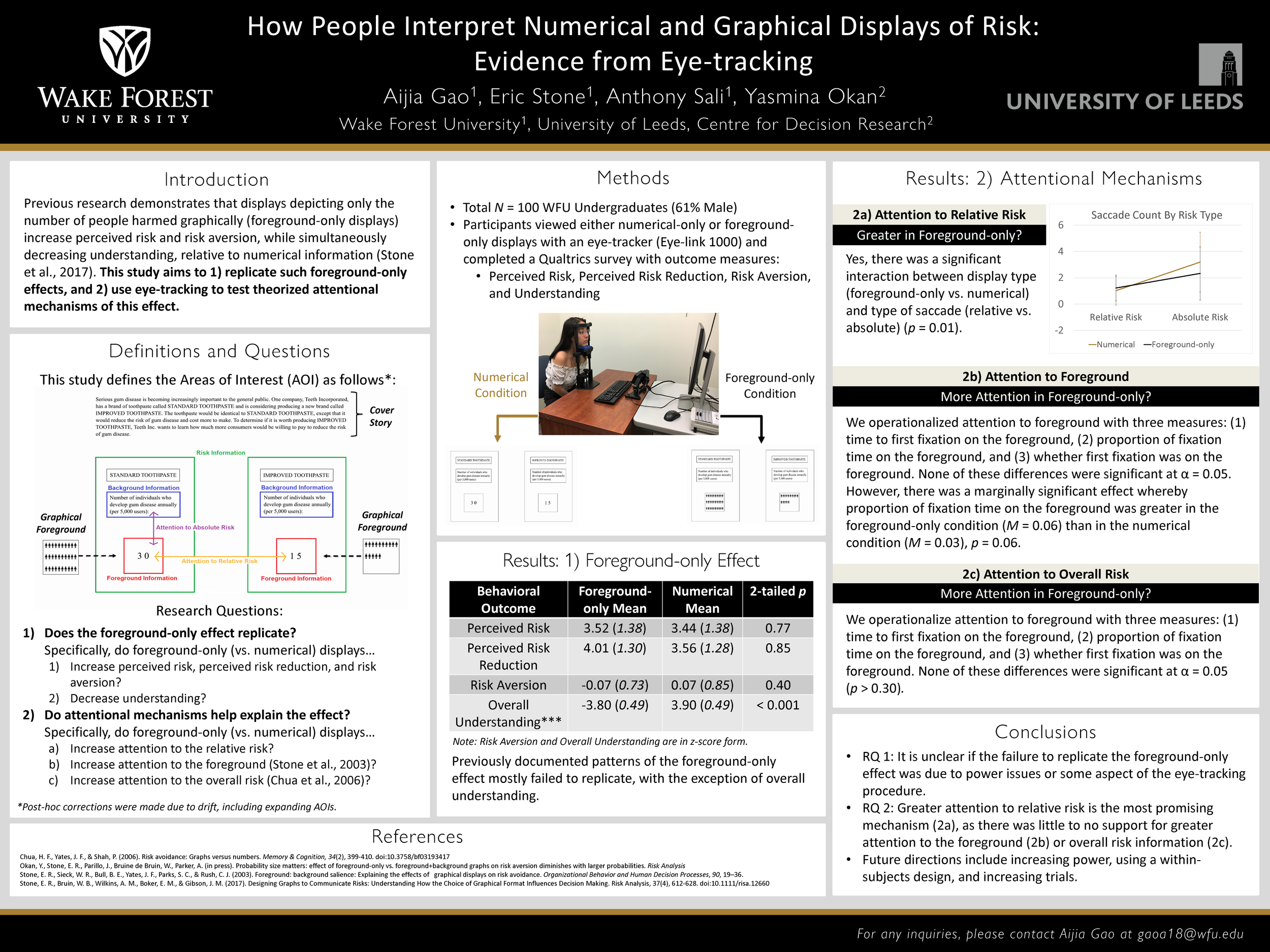

This is a “foreground-only” display, because it only displays the numerator visually in a low-probability risk ratio. This type of display is known to increase risk perception while lowering risk accuracy, which may be especially helpful for public health communicators in promoting risk averse behaviros, but may come at a cost of mystifying personal decision outcomes. Past work has proposed explanations for this effect, all referencing disproportionate capture of visual attention, but none have actually been tested. Thus, I lead an interdisciplinary collaboration using eye-tracking to investigate what people attend to when using such visual aids to make decisions.

Challenges: Learning how to design, run, and analyze an eye-tracking study under the constraints of a short master’s degree program was difficult, but thanks to the attentive guidance from a visual perception faculty (Dr. Sali), we were able to adapt a decision paradigm for our study. However, there were issues with translating eye-tracking metrics to make sense with social cognitive operationalizations of variables. Additionally, the primary effect of greater risk perception with certain visual aid designs were no longer consistently replicating when we adapted the study to use eyetracking.

Solutions and Takeaway: To better capture the psychological processes being measured, we focused on widening our scope while also using converging patterns to make conclusins. Specifically, we increased the areas of interest on the stimuli we are considering, but used compared across multiple attention metrics to make conclusions (e.g., first fixation, saccades, proportion of focal time spent, etc.). When doing so, we identified relative risk as a particularly salient piece of information that people use to draw conclusions from visual aids. Additionally, while the underlying risk perception effect was not consistently replicated, we interpreted this as a potential feature of the effect and are hoping to investigate whether certain conditions that induce greater attentiveness, or “slowing” of decision-making, can help reduce influences from visual aid design.